Hamilton celebrates 10 years since its Off-Broadway debut today, February 17, 2025. The opening number not only introduces the protagonist but also sets the tone and style of the show. Essential to the narrative, it summarizes the key events that shaped Alexander Hamilton’s life before his arrival in the United States.

Table of Contents

- History

- Music

History

Alexander Hamilton was born on January 11, 1755, one year before Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791). Throughout his life, he played a pivotal role in the American Revolution and the founding of the new nation, while also witnessing the French Revolution. Despite dying young at the age of 49, he achieved remarkable accomplishments—much like Mozart, who passed away at 35. The brilliance Mozart displayed in music, Hamilton displayed in writing.

“Hamilton’s mind always worked with preternatural speed. … His papers show that, Mozart-like, he could transpose complex thoughts onto paper with few revisions.”

Ron Chernow

But there is a crucial difference between these two prodigies—one that makes Hamilton’s story even more remarkable: his humble origins. While Mozart was a child prodigy, nurtured from an early age by his father, Hamilton had to overcome abandonment, orphanhood, and poverty to earn his place in history.

His Parents

Alexander Hamilton was an illegitimate child, the son of Rachel Faucette and James Hamilton.

Rachel Faucette: The Determined and Inteligent Mother

Rachel Faucette was born around 1729 and was the sixth of seven children. Her parents, Mary Uppington and John Faucette, married on August 21, 1718, in Nevis.

There is evidence that John and Mary often fought, possibly worsened by the loss of five of their seven children in early childhood and the economic crisis caused by an agricultural plague that struck the island in 1737. With frequent diseases ravaging the island, the Faucettes’ only surviving children were Rachel and her sister Ann, who was more than ten years older.

Mary Faucette, Rachel’s mother, deeply disliked the stagnant life she led with her husband, John Faucette. Determined to improve her social and financial standing, she filed for a legal separation from her husband with the Chancellor of the Leeward Islands. Following the 1740 agreement, in which the couple agreed to “live separately and apart from each other for the rest of their lives,” Mary took her daughter Rachel to St. Croix, where her eldest daughter, Ann, lived.

Ann Lytton, Rachel’s older sister, had prospered in St. Croix. Alongside her husband, James Lytton, she owned an estate called the Grange in the capital, Christiansted. It is likely that Mary and Rachel met Michael Lavien through the Lyttons.

In that 1740 legal separation agreement, Mary had renounced all rights to her husband’s property. Five years later, John Faucette passed away, making the sixteen-year-old Rachel Faucette the heir to a “considerable fortune.”

“A Dane, a fortune hunter of the name Lavine, came to Nevis bedizzened with gold and paid his addresses to my mother, then a handsome young woman having a snug fortune.”

Alexander Hamilton

Deceived by Michael Lavien’s appearance, Mary arranged the marriage between him and her daughter, against Rachel’s will. In 1745, at the age of 16—the same year she inherited her fortune—Rachel married Michael Lavien at the Grange. He was at least twelve years older than her. The following year, their only child, Peter, was born.

It was “a hated marriage,” in Hamilton’s own words. Michael Lavien, terrible with finances and investments, rapidly squandered Rachel’s inheritance, sinking deeper into debt at an alarming pace. Deeply unhappy in her marriage, the young Rachel fled home around 1750. Enraged and vengeful, Lavien had his wife imprisoned under a Danish law that allowed such action in cases of adultery.

We must pause for a moment to address the horrors committed within that prison.

Christiansvaern, the fortress of Christiansted, was a place where enslaved people were subjected to the most horrific punishments for any hint of insubordination. Standing on the edge of Gallows Bay, the fort served as a site of unspeakable cruelty. There, enslaved individuals were “whipped, branded, and castrated, shackled with heavy leg irons, and entombed in filthy dungeons.”

Rachel spent months imprisoned there, and it is difficult to imagine the horrors she must have witnessed and heard. By all accounts, Rachel was the only woman ever imprisoned for adultery at Christiansvaern. She never denied her husband’s accusations, leading many to believe that she had, in fact, been unfaithful.

However, if Lavien’s intention was to teach his wife a lesson through imprisonment, he only succeeded in deepening Rachel’s resentment toward him. Upon her release in 1750, the young Rachel spent a week with her mother in St. Croix. Shortly after, she abandoned her husband and son, leaving for Saint Kitts with her mother. It was there that she would meet James Hamilton.

James Hamilton: The Easygoing and Lackadaisical Father

Alexander Hamilton’s grandfather, also named Alexander Hamilton, was the fourteenth laird of the Cambuskeith branch of the Hamilton family.

The Hamilton family of Cambuskeith had a coat of arms and owned a castle for several generations, known as the Grange (yes, the same name as James Lytton’s estate, though they were different places). In 1685, the family took possession of Kerelaw Castle.

In 1711, Alexander Hamilton (the grandfather) married Elizabeth Pollock, the daughter of the baronet Sir Robert Pollock. The couple had eleven children, with James Hamilton being the fourth son.

James Hamilton grew up as a nobleman at Kerelaw Castle. During his childhood, the family estate included farmland and a textile industry. However, as the fourth son, he was unlikely to inherit the Grange.

From a young age, James Hamilton seemed to lack the ambition or skill that would lead his brothers to comfortable positions in society. Between the ages of 19 and 23, he worked as an “apprentice and servant” for a merchant in Glasgow, Scotland. His apprenticeship contract was arranged by his eldest brother, John Hamilton. When the contract ended in 1741, James Hamilton decided to head to the West Indies, hoping to make his fortune as a merchant.

Although he enjoyed some initial success in his ventures, James soon faced the harsh realities and risks of agricultural trade in the region. By 1748, his career had collapsed entirely, and he would need to remain there much longer, working as an employee, to pay off his debts.

The parallels between the lives of James Hamilton and Rachel Faucette likely drew them together when they met in the early 1750s. Rachel, having fled from her husband, could not legalize her relationship with James, as obtaining a divorce was both costly and difficult at the time.

Birth of Alexander Hamilton

For a long time, it was believed that Alexander Hamilton was born in 1757, a date he himself claimed after arriving in the United States. However, various records from his time in the West Indies suggest that he had added two years to his age. Historian Ron Chernow, based on these indications, concludes that Alexander Hamilton was born on January 11, 1755.

The Horrors of Slavery

Alexander Hamilton’s life on the islands was filled with horrifying images of violence under slavery. Enslaved people could be branded with hot irons, castrated, or whipped hundreds of times. If they raised a hand against a white person, their hand was cut off; if they attempted to escape, one foot was amputated—and if they tried again, the other foot followed. It was as if slave owners sought to constantly remind the enslaved of their subjugation. Any captive who assaulted a white person was executed, either by hanging or decapitation. The environment in which young Alexander grew up was so violent that it shocked visitors—a brutal backdrop that would profoundly shape his worldview.

Because Alexander’s maternal grandmother had passed away, Rachel became the owner of five enslaved people, whom she rented out to supplement her income. Among them were four children, one of whom—a boy named Ajax—was assigned by Rachel to be Alexander’s personal servant. From an early age, Alexander witnessed both the humanity of the enslaved and the cruelty of their white oppressors.

The Father’s Abandonment

In April 1765, James Hamilton took on a business assignment in Christiansted and brought his family with him. His task was to collect a large debt from a man who denied owing money to the family of Archibald Ingram, James Hamilton’s former employer. While the legal dispute dragged on, Rachel and their children lived in Christiansted—the same town where Rachel had once lived with Michael Lavien. In a place that already knew her past, she could no longer hide the scandal of her concubinage. During this time, Peter and Alexander likely felt even more deeply the stigma of their illegitimacy.

When the case was finally resolved, with James Hamilton’s side victorious, he abandoned his family forever. The true reason for his sudden departure remains unknown, but Alexander Hamilton would later surmise that his father simply could no longer support them. James Hamilton left for another island in the Caribbean but never managed to leave, likely trapped by poverty.

Alexander was 10 years old, left to rely solely on his mother and her family.

The Death of His Mother

Ann Lytton, Rachel’s sister, and her husband, James Lytton—former owners of the Grange in Christiansted—were forced to sell their estate after a failed business venture by their second son, James Lytton Jr. With the most successful branch of Hamilton’s family now in financial trouble, they could no longer offer much support to Rachel and her two sons. Ann Lytton would never have the chance to help her sister, as she passed away in 1765.

With determination and courage, 36-year-old Rachel turned the ground floor of their home into a provisions store for local farmers—an uncommon achievement for a woman at the time. But her journey was cut short in early 1768 when she contracted an unknown illness, which soon afflicted Alexander as well.

After a week of severe fever, the woman caring for Rachel summoned a doctor on February 17. The medieval-style treatments of Dr. Heering proved ineffective, and at 9 p.m. on February 19, 1768, after days of vomiting and diarrhea, Rachel died, with her 12-year-old son Alexander by her side.

Alexander recovered in time to attend his mother’s funeral alongside his brother. Yet, Rachel’s death did not bring an end to the family’s debts. Probate court agents visited the home to assess the estate, which was soon auctioned off. It was Alexander’s uncle, James Lytton, who purchased Rachel’s book collection to ensure it remained with the boy—a treasure he deeply cherished.

A year later, the court awarded the remainder of Rachel’s estate to Peter Lavien, her son with Michael Lavien. Peter, Alexander’s half-brother, showed complete indifference to the Hamilton orphans, never offering them any financial support.

“Moved in with a cousin…”

The orphaned brothers went to live with their cousin, Peter Lytton, the son of Ann Lytton. Peter, who had also suffered a series of business failures, committed suicide on July 16, 1769. In his will, he left nothing to Alexander and James.

Grieving the loss of both his wife and son, James Lytton appeared to claim the inheritance, intending to help the orphans. However, his son’s suicide created legal complications. On August 12, 1769, James Lytton also passed away. In the will he had written just five days earlier, he, too, left nothing to the orphans. Alexander Hamilton was only 14 years old.

“They placed him in charge of a trading charter”

The death of their uncle caused the brothers to part ways. James became an apprentice carpenter—a trade that white men typically avoided at the time—while Alexander began working for the mercantile firm Beekman and Cruger (later known as Kortright and Cruger), the suppliers of his late mother’s store.

As a clerk, Hamilton managed inventory records, handled financial operations, planned shipping routes, supervised cargo loading and unloading, and calculated prices across different currencies.

Hamilton’s competence was so remarkable that, at just 16 years old, he was placed in charge of the company when Nicholas Cruger traveled to New York in October 1771. For five months, Hamilton made quick decisions and did not hesitate to reprimand subordinates—many of whom were far older than he was. Eager for leadership, he likely felt disappointed when Nicholas Cruger returned to St. Croix in March 1772.

Literature, Writing, and the Hurricane

From an early age, Alexander was a boy who loved books. Amid a violent and impoverished environment, Hamilton found solace in other worlds, reading the poetry of Alexander Pope, The Prince by Machiavelli, and Parallel Lives by Plutarch. The earliest known piece of writing by Hamilton is a letter to his friend Edward Stevens, dated November 11, 1769, which already reveals the young clerk’s talent for writing.

On April 6, 1771, the Royal Danish American Gazette, which had begun publishing the previous year, printed two poems by Alexander Hamilton at his own request.

Perhaps it was through the Gazette that Hamilton met a Presbyterian minister named Hugh Knox, who would become a major benefactor in his life. Knox opened the doors of his personal library to the young Alexander and encouraged him to write poetry and pursue his studies.

On August 31, 1772, a devastating hurricane struck St. Croix. On September 6, Hugh Knox delivered a sermon of comfort to the congregation, which was later published as a pamphlet. Deeply moved by the sermon, Hamilton wrote a long and vivid letter to his father, describing the terror of the hurricane.

Knox, impressed by the power of Hamilton’s writing, urged him to allow its publication in the Royal Danish American Gazette. The letter appeared on October 3, accompanied by an introduction attributed to Knox himself.

Unknowingly, Hamilton—who had been reluctant to publish the letter—had just written the first chapter of his way out of poverty.

Headed for a new land

Faced with the devastation caused by the hurricane, which plunged St. Croix into a prolonged economic crisis, Hugh Knox launched a campaign to fund Hamilton’s education in New York. The power of the young man’s story and his talent with words moved the community, inspiring many to contribute generously. Thanks to their support, the fund raised enough money to send him to the mainland and cover his education.

Hamilton’s journey to the mainland lasted three weeks, landing at the port of Boston. From there, he traveled to New York, where he sought financial assistance from Kortright and Company, the New York branch of Kortright and Cruger, which would help him take his first steps toward a new life.

Music

“He’d taken the first 40 pages of my book and condensed them into a four and a half minute song.”

Ron Chernow, in an interview with the Center for Brooklyn History

The opening number of Hamilton is a masterpiece of concision—and it was also the first song Lin-Manuel Miranda wrote for the project. It premiered on May 12, 2009, at the White House Poetry Jam.

At the time, Lin-Manuel described the project as a concept album. In its earliest version, the character Burr sang the entire song alone. However, he later realized he was actually writing a musical—a story that would be told not only by Hamilton’s enemies but also by his friends and those closest to him. As a result, the version that reached the stage features multiple characters sharing the narration.

Before the lyrics begin, the music imitates the sound of a door closing and slamming. Lin-Manuel took an audio file called “Door Wood Squeak” from his computer’s music software and transformed it into musical notes.

From that point, the characters begin to sing in a style reminiscent of the opening number from Sweeney Todd.

This song by Stephen Sondheim was a key inspiration for Lin-Manuel, who aimed to open the number by establishing the world of the musical through both lyrics and musical style.

Time

From the moment Hamilton begins working for Beekman and Cruger, he starts to see the world differently. Lin-Manuel Miranda compares this period in his life to the moment Harry Potter discovers he is a wizard: suddenly, a whole new universe of possibilities unfolds before him. With access to Hugh Knox’s library, Hamilton reads voraciously, sharpens his administrative skills as a clerk, writes poetry, and studies intensely.

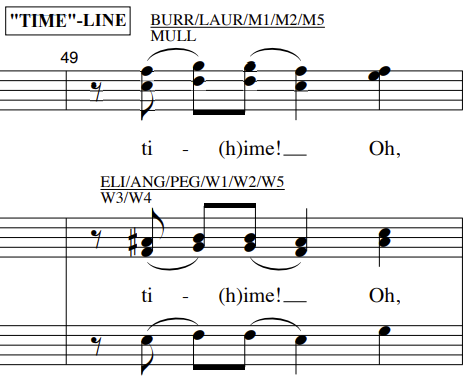

This is also the point where the music reflects his internal transformation. Lin-Manuel tells they “double the tempo here because Hamilton’s found his way out”. The beat remains steady, with continuous sixteenth notes, but the density of the lyrics increases. It feels as if Hamilton is squeezing more thoughts into each measure—the time, though unchanged, feels shorter. As Lin-Manuel puts it, this is the moment when “everything suddenly makes sense,” and Hamilton chooses to make every second count, doubling his dedication and urgency.

The word “time” is central to this musical, repeated dozens of times throughout the show. Right in the opening number, the entire cast, standing and facing the audience, sings “time” in the line: “You never learned to take your time!” The word is stretched across the measure, foreshadowing the significance of this theme in Hamilton’s story.

Characters

In the musical, some characters are played by the same actor, creating thematic parallels between friendship, rivalry, and sacrifice.

- “We fought with him” is sung by the actors portraying:

- Hercules Mulligan and Marquis de Lafayette – Hamilton’s friends, who fought with him, by his side.

- James Madison and Thomas Jefferson – Hamilton’s political rivals, who fought with him, or rather, against him.

- “Me? I died for him” is sung by the actor portraying:

- John Laurens, who died on August 27, 1782—not directly for Hamilton, but for the cause of the American Revolution. On August 15, 1782, Hamilton had urged Laurens to join him in politics: “Quit your sword my friend, put on the toga, come to Congress. We know each others sentiments, our views are the same: we have fought side by side to make America free, let us hand in hand struggle to make her happy.” However, Laurens may have died before he ever had the chance to read this letter.

- Philip Hamilton, Alexander Hamilton’s son, who died on November 24, 1801, in a duel with George I. Eacker, defending his father’s honor. Eacker had insinuated that Hamilton would use his army to remove Thomas Jefferson from power. When Philip confronted him, Eacker insulted both Philip and his friend, Price. Determined to defend his father, Philip ultimately gave his life for him.

The line “I’m the damn fool that shot him” succinctly conveys the regret of Aaron Burr, who shot Hamilton in a duel on July 11, 1804. Hamilton died hours later, on July 12. The real-life Burr was known to say: “My friend Hamilton, whom I shot.”

Alexander Hamilton has, in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s words, “an absurdly musical name.” The three notes preceding his name in the line “My name is Alexander Hamilton” shape his introduction into iambic pentameter, the rhythm most commonly used by Shakespeare in his poetry.

The final line of the song is the name of our protagonist. Now that Hamilton, “another immigrant coming up from the bottom,” has arrived at the port of Boston, he sets off for New York—the city where he “can be a new man.”

Leave a Reply